Joanna Arvaniti

Aleksandra Wójtowicz

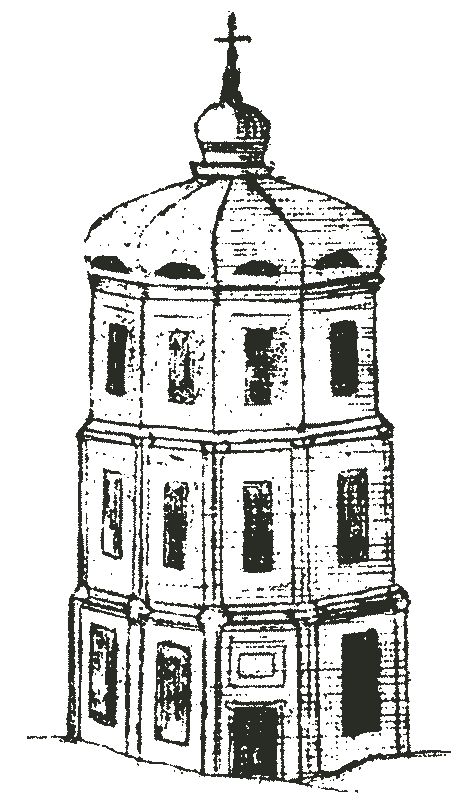

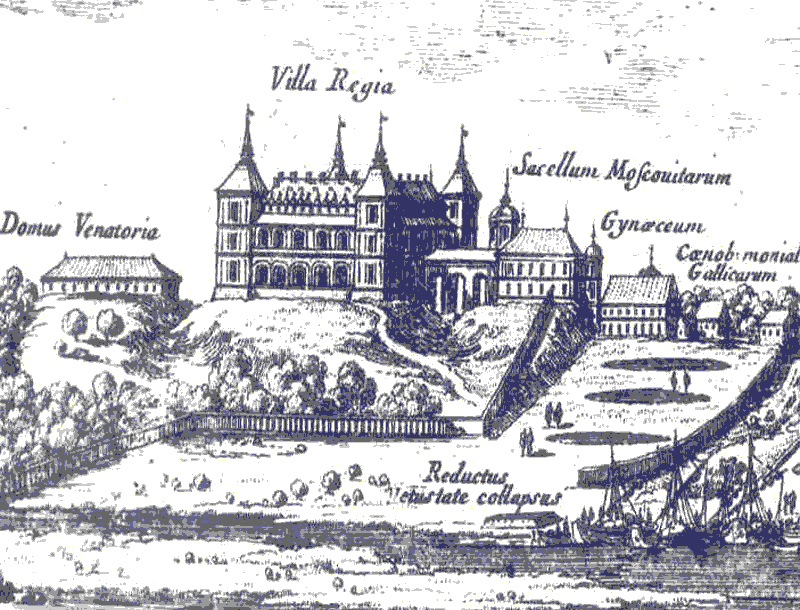

The Moscow Chapel was built by order of King Sigismund III Vasa at a strategic point on the route leading from the Royal Castle towards Ujazdów. The bodies of tsars Vasyl and Dmitri Shuisky as well as Dmitri’s wife Catherine, who were taken prisoner following the Polish-Russian Battle of Klushino in 1610 and died in 1612 at the castle in Gostynin, were buried there. The bodies of the tsars were returned to the Russians by King Wladyslaw IV in 1635, and the building deteriorated and fell into oblivion.

According to some sources, the Moscow Chapel existed until 1954 in the form of a building located at the back of the Staszic Palace. According to others, the building was a former summerhouse of the Słuszko family or an icehouse, while the chapel itself was included in the complex of the church and monastery of Observant Dominicans, on the ruins of which the Staszic Palace was built.

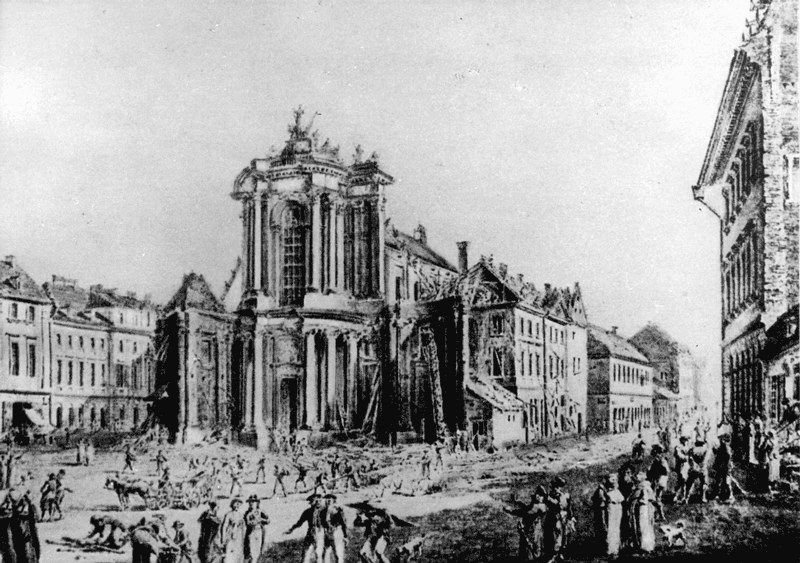

The Church of Our Lady of Victory, together with the monastery and cemetery, existed on the site of today’s Staszic Palace from 1700 to 1818. Until 1813, it belonged to the Observant Dominicans, brought to Warsaw by King John Casimir following his victory over the Swedes. It was demolished in 1818 after profanation by the suicide of Father Danikowski, the church administrator, who took his own life on the altar of the temple.

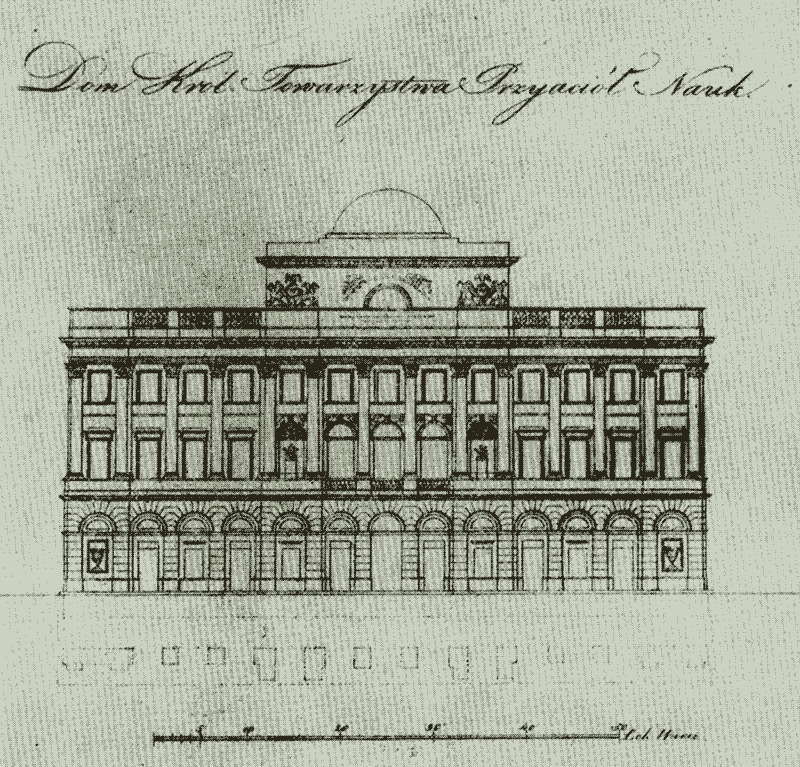

The building in Krakowskie Przedmieście was originally designed as the seat of the Warsaw Society of the Friends of Learning (Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk), which existed from 1800 to 1832 when, as an act of repression subsequent to the November Uprising, Tsar Nicholas I declared it non-existent and confiscated the Society’s collections located in the palace. In the first period of its existence, the Society met in the house of Stanisław Sołtyk and its first president, Jan Chrzciciel Albertrandi, and later in tenements in Kanonia Street, bought for this purpose by Staszic. Open meetings of the Society were then organized in the library of the Piarist Fathers in Miodowa Street.

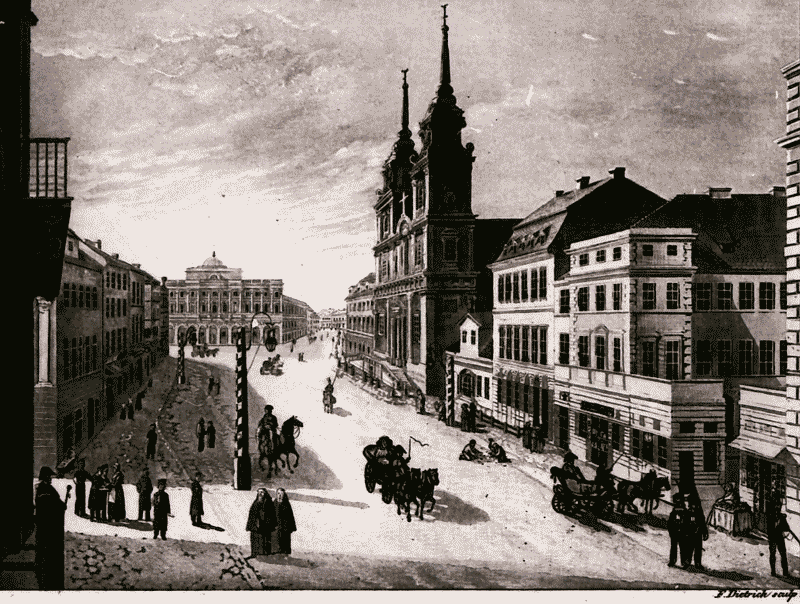

The empty square left by the demolished church was bought by Stanislaw Staszic in 1818, based on a decree approved by Tsar Alexander I, to build the seat of the Warsaw Society of the Friends of Learning. In 1820, the cornerstone for the palace was ceremoniously dug in, and the first meeting of the Society in the building designed by Antonio Corazzi took place in 1823. The year 1824 marked the date of the first meeting open to the public, gathered in the amphitheater meeting room of the Society.

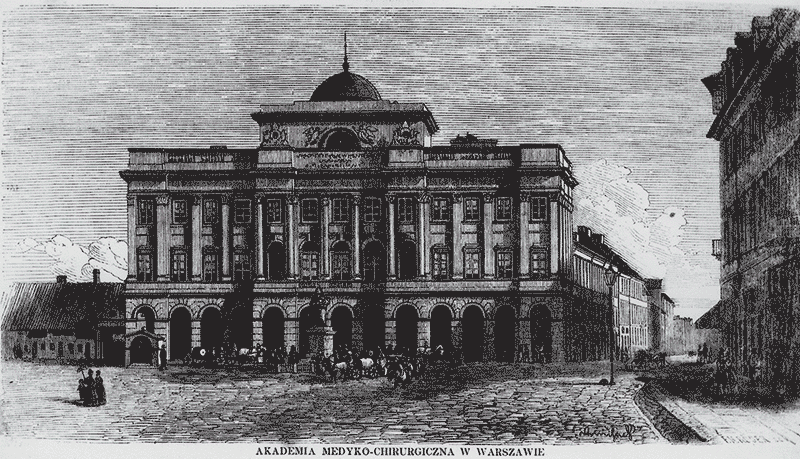

Following the dissolution of the Warsaw Society of the Friends of Learning and the period when the Lottery Directorate was located in the building (formally from 1835), the Academy of Medicine and Surgery as well as the faculty of the Main School were transferred to the building in 1857. However, the meeting room converted into an assembly hall proved to be too large for school classes. In terms of acoustics and temperature, it also did not meet the requirements of the then rector, therefore in 1862 it was decided to convert the building into a Russian men’s gymnasium with an orthodox church and a boarding school.

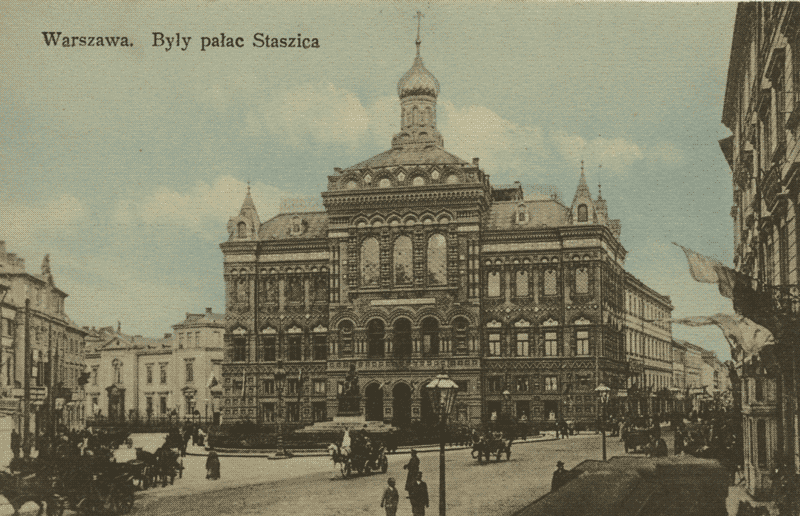

The 1st Men’s Gymnasium, known as the “Russian” Gymnasium, located in the building of the former Society, was officially established in 1865, converting a room on the 2nd floor into a house orthodox church devoted to St. Cyril and Methodius. However, the room proved too small, and the church was moved to the first floor in 1877. In the 1890s, upon the initiative of Alexander Apukhtin, superintendent of the Warsaw school district, a plan was drafted to transform the building in Byzantine-Ruthenian style and erect a church of St. Tatiana the Roman. To this end, the former meeting hall of the Society was transformed into a church interior and richly furnished, and the reconstruction of the palace, according to the design of Vladimir Pokrovsky, began in 1893. The interior layout and appearance of the building were completely changed, the exterior façade was replaced by a majolica church façade, and a gilded dome with ten bells was erected on the bell tower. The church was consecrated in 1899.

The land surrounding the square in front of the palace from the east side (known as “Kabatek” in the 18th century) was purchased by Kazimierz Karaś – administrator of the crown post office, member of the treasury committee of the table estate, and private marshal of the royal court of Stanisław August. In 1771, he built a palace on the site. The two-story Renaissance-style building with fifteen windows, a facade with five windows and decorative cannons at the corner gates had the only baroque balcony made of wrought iron in Warsaw at that time. In 1772, a corps of pageants was stationed in the palace. After the owner’s death, the palace passed from one owner to another, and at the end of the 19th century, there was a tavern commonly known as “u Karasia” (at Karas’s), visited by carriage drivers who would stop at the square. One wing of the building was demolished in the early 20th century, and it was planned to convert it into a museum; later it was sold for the construction of profitable tenement houses. The palace was demolished before World War I.

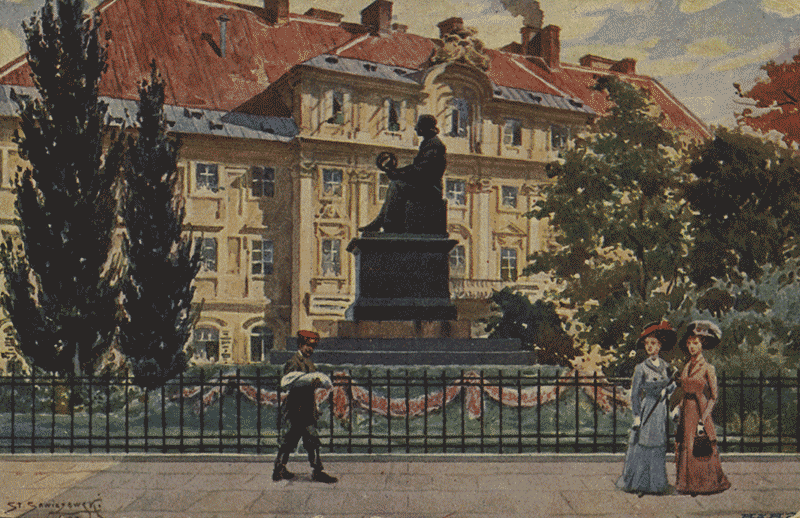

The question of commemorating Copernicus was raised at a meeting of the Society in 1810. A monument to the astronomer was part of Staszic’s overall plan to erect it in front of the seat of the Warsaw Society of Friends of Learning. There were several drafts of a statue of the astronomer that were not completed, including those by the palace designer Antonio Corazzi and Piotr Aigner. The contract for the existing monument by Bertel Thorvaldsen was signed in 1820 during the Danish sculptor’s visit to Warsaw; he was working on the monument to Prince Józef Poniatowski. The author of the pedestal, selected from many, was Adam Idzkowski. Despite the public fundraising for the erection of the monument and the financial contribution of the Society, the design was completed only after Staszic’s death, owing to the amount he donated for the cause in his will. In 1830, a ceremony was held to unveil the Copernicus monument; a speech was delivered by Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, president of the Society at that time.

During World War II, under occupation, the inscription on the Copernicus monument was replaced by a German plaque with the inscription Dem grossen Astronomen, which was secretly removed in 1942 by Grey Regiments scout Aleksy Dawidowski as part of an independence campaign. In 2017, a plaque commemorating this event was erected at the monument. Another action of 1943, as part of which poets Tadeusz Gajcy, Zdzisław Stroiński and Wacław Bojarski placed white and red flowers at the monument, cost Bojarski his life. The destroyed Copernicus monument together with the statue of Christ from the Holy Cross Church were taken away from Warsaw by the Germans. The statues, abandoned in Silesia, were found in 1945 and put back in their original place. The Copernicus monument was renovated under the direction of Stanisław Jagmin and unveiled again in 1949.

XX

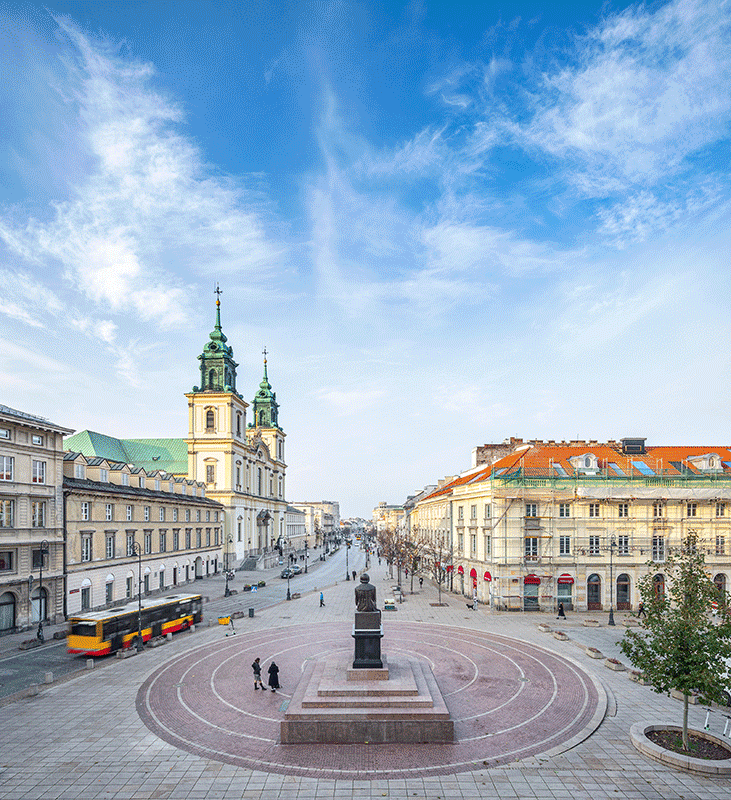

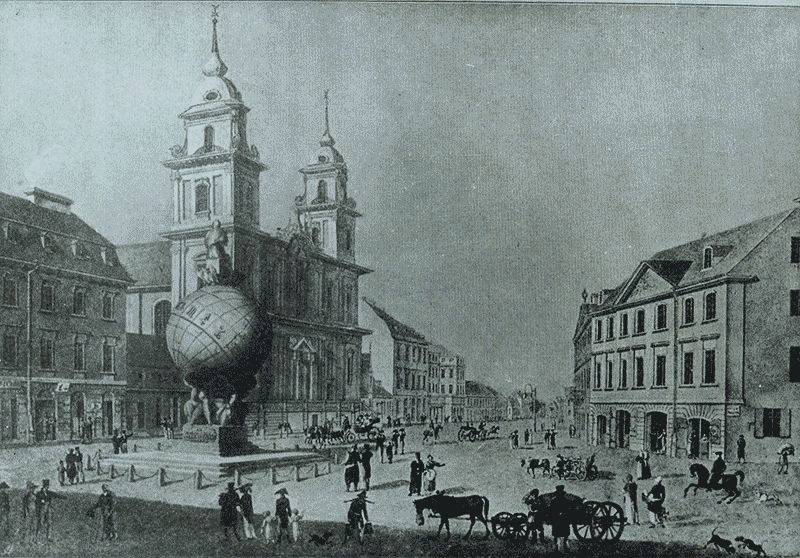

The Holy Cross Church and the Staszic Palace, together with the statues of Christ and Copernicus, form a system of architectural structures with a similar semantic and symbolic load. Sacralization and desacralization were important aspects of the historical transformation process, reflected in the activities carried out also on the square in front of the palace. This space was the venue of events important to the nation’s history, where patriotic values often coalesced with religious ones. Of the buildings forming the various frontages of the square, the Holy Cross Church was erected first in 1525 (the Holy Cross Chapel had existed since 1510).

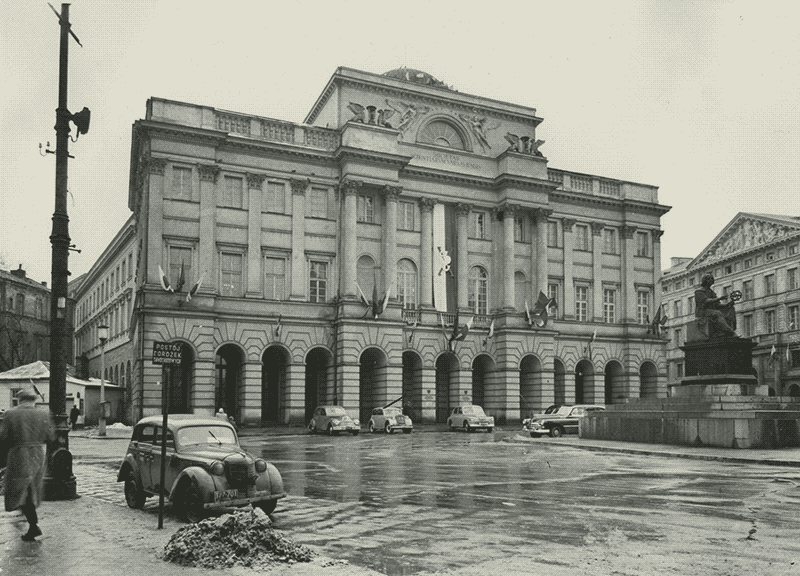

In the 1920s, Franciszek Pułaski, a member of the Warsaw Scientific Society, chaired the Executive Department of the Committee for the Restoration of the Staszic Palace. The former seat of the Warsaw Society of the Friends of Learning, recovered upon Poland’s independence, was transferred to the Warsaw Scientific Society pursuant to a 1919 resolution executed in 1924. The Committee for the Restoration of the Staszic Palace set a schedule of works so that a commemorative plaque would be unveiled on the restored edifice to mark the 100th anniversary of Stanisław Staszic’s death. The ceremonial unveiling took place as planned on January 26, 1926.

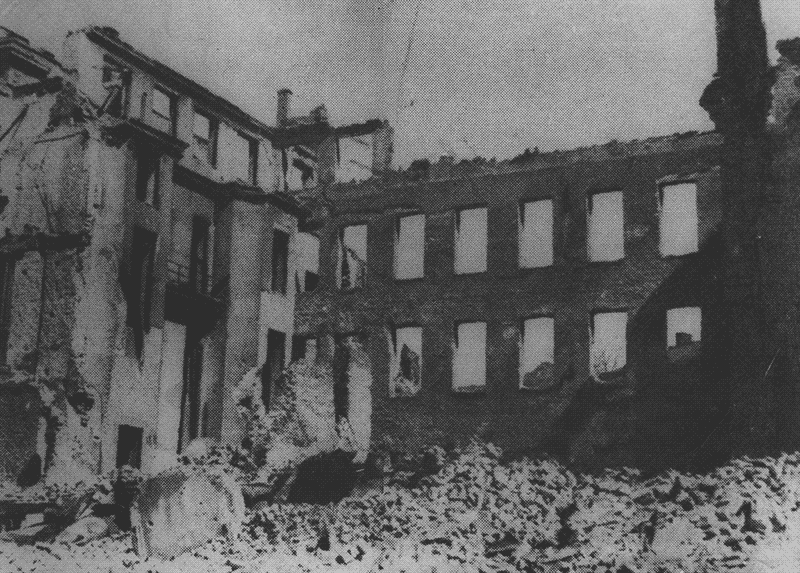

As a result of the warfare, the Staszic Palace was destroyed and burnt inside; yet, the structure survived. The part of the building facing Nowy Świat was completely destroyed by a bomb explosion. The bomb also damaged part of the dome and the rooms on the top floor. During the post-war reconstruction, under the direction of architect Piotr Biegański, the palace was renovated and extended with newly added wings leading towards Świętokrzyska Street.

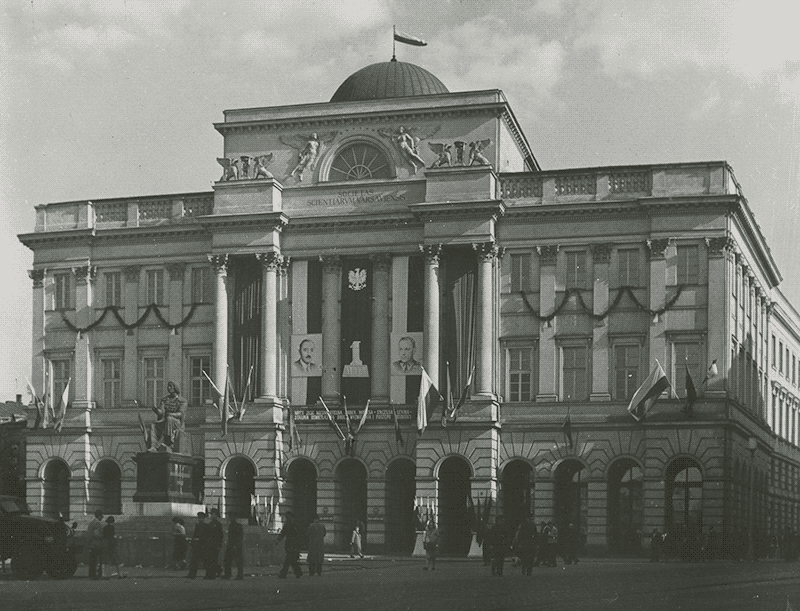

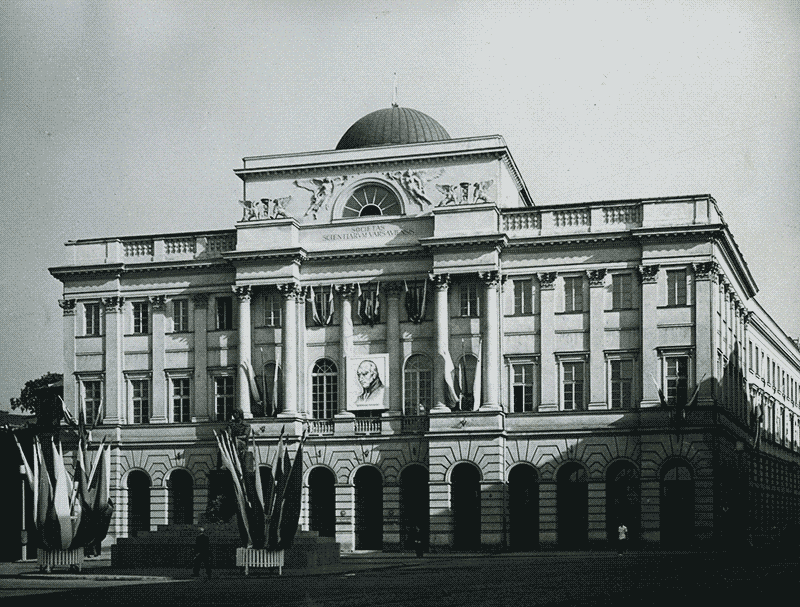

Throughout the history of the Staszic Palace, activities caused by changes in the political system collided, coexisted, and superseded each other. However, the purpose of existence of the institution it was originally built for, i.e. scientific work, determined the final purpose of the building. Today it serves as the seat of the Polish Academy of Sciences and the Warsaw Scientific Society, continuing the mission of the historic Warsaw Society of the Friends of Learning. The pictures show the Staszic Palace during the Copernicus Year and the Socialist International Labor Day celebration in 1953, and with an image of Stanisław Staszic on July 22 of that year.

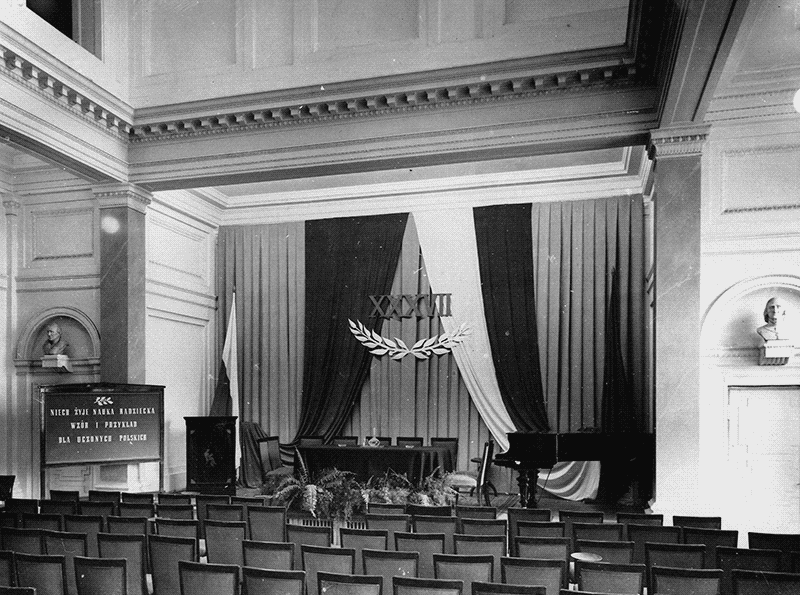

1953 PAN Scientific Session “Revival in Poland” in the Hall of Mirrors, motto adopted from Frycz Modrzewski; “The Republic of Poland shall not survive without science”. and the 37th anniversary of the October Revolution celebrated in 1954 in the Hall of Mirrors under the motto “Long live Soviet science – a model and example for Polish scientists”.

The initial design of the Staszic Palace included only the main mass on a rectangular plan. The wings leading south to Świętokrzyska Street are a solution designed by architect Piotr Biegański and constructed during post-war palace reconstruction. In the distance, behind the Copernicus monument, you can see the building of the Arnold Szyfman Polish Theatre, designed by Czesław Przybylski (1912).

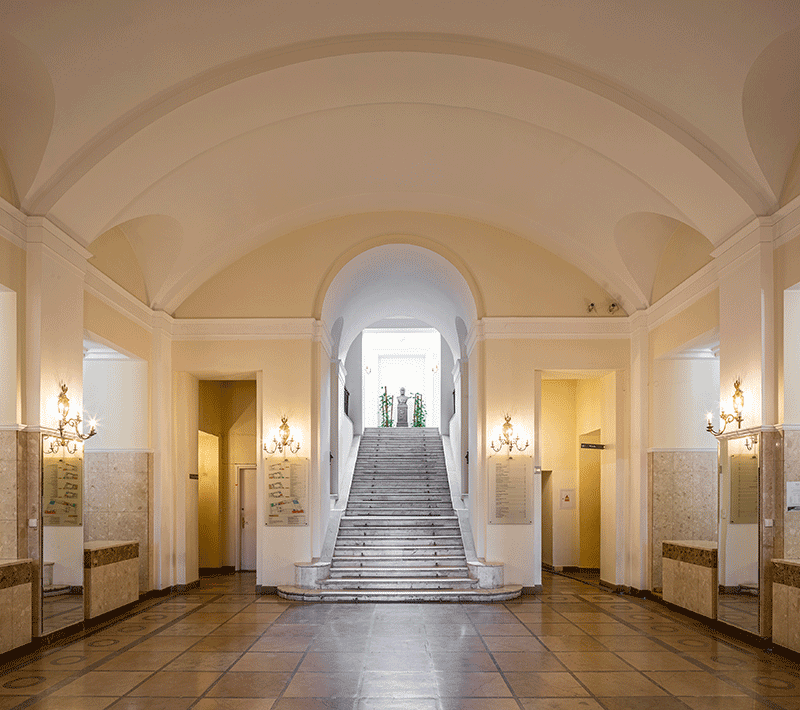

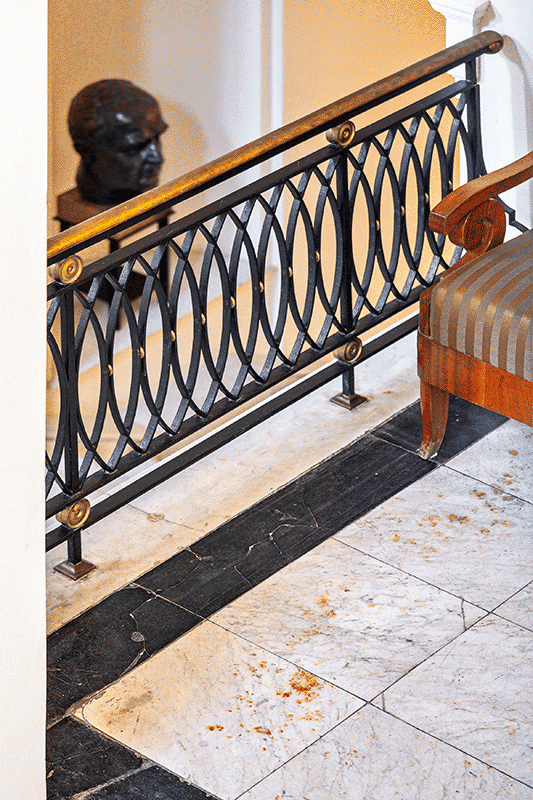

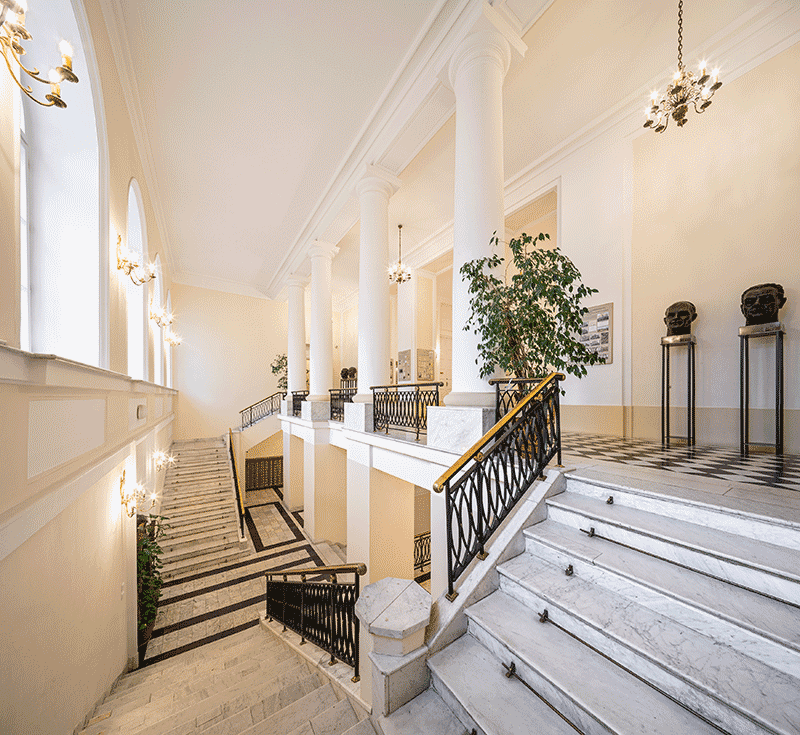

The present layout of the lobby differs from the former palace interior. In the original shape, Antonio Corazzi arranged empire-like Italian-style stairs with handrails made of cast iron on one side adjoining the main entrance. During palace reconstruction according to Pokrowski’s plan, the layout of the staircase was changed, providing direct inter-floor access to the Orthodox church located on the second floor. The present shape of the lobby was determined during the restoration in the 1920s and reconstruction in the 1940s, with the staircase moved to the wall on the southern side.

The floor of the Staszic Palace bears traces of the blood of insurgents who fought to defend it from August 23, 1944 to September 6/7, 1944. Research conducted upon the initiative of Krzysztof Kosiński, PhD, IH PAN, and Zbigniew Tucholski, PhD, IHN PAN, has revealed that this is human blood, preserved on the marble slabs. It can be found not only on the mezzanine; for example, there is a bloody human hand print in a niche by the stairs. The Staszic Palace served as an insurgent stronghold during the action held in August 1944, which is described by K. Kosiński in his article Pałac Staszica w czasie wojny (“The Staszic Palace during the war”). In the photo, you can also see a fragment of the former balustrade.

In place of the now existing space above the staircase at the level of the first floor, the original form of the building housed an amphitheatrical meeting room, accommodating several hundred people. From the north, it bordered on the mineralogical office, whose windows overlooked Krakowskie Przedmieście, while the presidium part covered the area up to the southern wall of the building. The picture shows neoclassical columns, which harmonize with the colonnade of corazzia, recreated in the Hall of Mirrors. The sculptures of the heads of Polish scholars are an exhibition of the collection by Zofia Wolska.

In the Hall of Mirrors, you can see historical exhibits, such as the rostrum with the logo of the Warsaw Scientific Society or 19th century sculpted busts of Polish scholars. The communication node and the lobby in front of the hall are solutions introduced by Piotr Biegański after World War II. Circular windows facing south were designed so that on sunny days the lighting effect would expose one of the most important places in the building – the space in front of the Hall of Mirrors. The picture shows the permanent exhibition, prepared by the PAN Archive, presenting the history of the Staszic Palace.

The view looking out of the Hall of Mirrors window of the Staszic Palace towards Krakowskie Przedmieście Street is one of the most popular shots of Warsaw. The perspective towards the Royal Castle from a point located here is a look known from paintings by Canaletto. It permits a different perspective on the edifice of the Holy Cross Church and the Nicolaus Copernicus monument, as well as a full view of the intention of sculptor Antoni Grabowski, the author of a design based on placing the model of the Solar System taken from Copernicus’ work “On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres” (2007) in the floor of the square.